mail[at]wolfgangkowar.de

Discovery and Invention

On the Oeuvre of Wolfgang Kowar

Michael Stoeber

Wolfgang Kowar concludes notes he wrote about his artistic work with a wish that can unfortunately no longer be fulfilled: “If only Francois Dufrêne and Raymond Hains could see my works!” They cannot, as they have both died in the meantime. Yet this sincere wish demonstrates how Kowar sees his artistic roots and reveals the line of tradition to which his oeuvre adheres.

Dufrêne and Hains are members of the Nouveau Réalisme movement, a group of artists who joined forces around the critic Pierre Restany in 1960 in Yves Klein’s Paris apartment. Like Jacques de la Villeglé and the Italian Mimmo Rotella, they are affiche (French for “poster”) artists, as they find the raw material for their art in the advertising posters displayed in cities.

The posters are regularly pasted, one over the other, onto advertising spaces. It often happens that delightful constellations of images randomly emerge when the elements or the human hand tear at them to expose text or image fragments from underlying posters. The affiche artists were susceptible to such accidental discoveries. They peeled them away, stuck them onto canvas or other supports, and presented them to the public in the tradition of Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades.

Depending on the artists’ intellectual and emotional preferences, this by all means resulted in individual signatures. Mimmo Rotella publicized his passion for movie posters. Hains and Villeglé, on the other hand, preferred posters that criticized consumption and were politically agitating, while Dufrêne loved the unfettered play of colors and forms. In order to elicit the abstraction of his works, he liked to stick the reverse side of the posters onto his canvases.

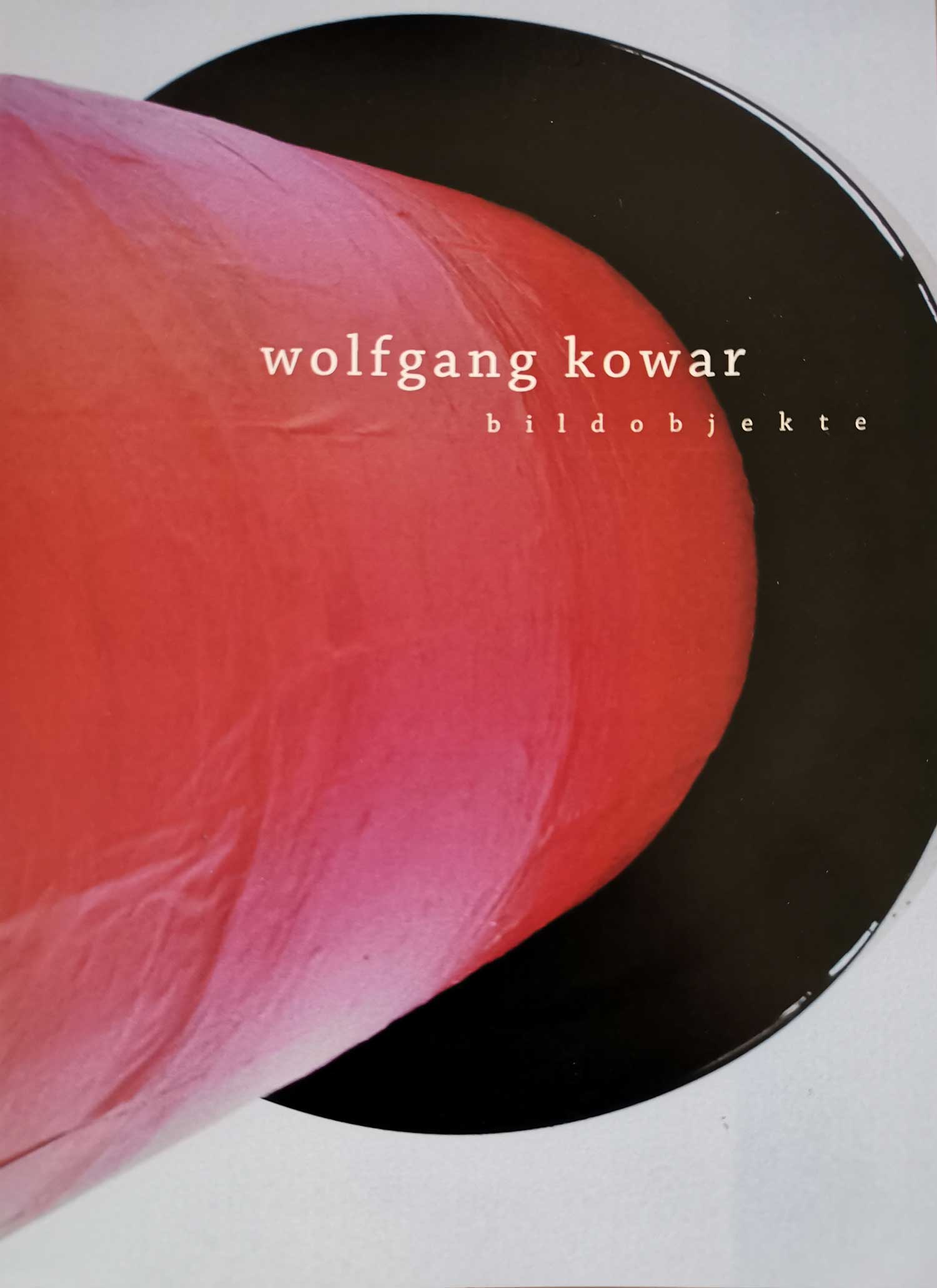

Of all the poster artists, this gesture places him in the greatest proximity to Wolfgang Kowar, whose artistic source material comes from advertising columns. He removes the centimeter-thick layers of posters that have accumulated over the years en bloc, and not, like the affiche artists, only the last two, three, or four posters. The sheaves of paper retain the curve of the column, thus Kowar’s treatment of his discoveries is a painterly as well as a sculptural one.

His works also exude this. They are at once painting and sculpture, and their hybrid character is consistent with the specific object—this is how Donald Judd described works located somewhere between the two artistic genres. Kowar’s works essentially afford the viewer three perspectives: for one, their form as a plastic object, and for another, their front as well as their reverse side, each of which is a separate picture in its own right.

Depending on the thickness of the sheaf of posters, decades may lie between the top and bottom layers. When Kowar cuts into the larger sheaves in order to extract his work, he feels like an archeologist. Yet his action is not about the reconstruction of a particular historical period. For the artist, the posters are a disposable aesthetic quantity and not a sociopolitical one.

His archeological cuts do not seek, they find. It is not by chance that this self-description is reminiscent of Picasso’s proud words: “I do not seek. I find.” While the latter finds because his ingenuity was a tirelessly bubbling source of inspiration for one new work after the other, Kowar finds because his material never wearies of supplying him with a constant stream of new stimuli.

He only has to decide which constellations of form and color he wants to select and flesh out in his works.

In the process, he is guided by the successful picture, which is achieved when the dramatic encounters between color and form produce a balance. When the excited lines that run through the picture settle down. When the chaos of the forms and colors from different periods and epochs yields to become timelessly harmonious, soothing the viewer’s eyes and bearing witness to the utopia of a cosmos that has always been art’s home.

In order to achieve this image, which is discovery as much as it is invention, Wolfgang Kowar cuts, mills, and smoothes away. He planes down the accumulated layers of paper, pastes together new ones, and grinds down the surfaces of his pictures. Mindfully and carefully. It is only in this way that their magic appears, which is always one of form. It allows numerous other images to surface from behind the current one, which becomes reality with the help of the artist’s hand; images that do become real until they have assumed form in the viewer’s imagination.